An individual is often described as an innovator if they exhibit a talent for entrepreneurial success. The innovator is often imagined as a bold, creative entrepreneur. The focussed, driven, hardworking nucleus of a new enterprise in possession of all the creativity and drive required to construct a viable and successful business. A visionary that is well rewarded for delivering a valuable product to a grateful customer.

Those entrepreneurs who labour to build a new business from scratch and those who have climbed to the very top of the corporate tree share a feature in common.

The freedom to dream.

Advice on the topic of innovation often seems directed to those free to propose exciting new business models in support of disruptive new ideas, whether these manifest in an established corporation or are proposed independently before sceptical venture capital.

However, I work within the bowels of a large, successful and well established corporation.

My contribution does not focus upon the diligent work of business-building but upon the discovery of that elusive great idea that connects the customer to a valuable product or service.

An individual may also be recognised as an innovator if they exhibit the chaotically creative talent required to understand and resolve intractable problems. A problem-solving mind so bursting with wild ideas that it can barely keep up with its output.

This role is not entrepreneurial at its core. This output is better described as invention and the activity is better described as diagnostic. This diagnostic role is better illustrated with the detective skills of Sherlock Holmes rather than the business acumen of the world’s current crop of Rockstar Entrepreneurs.

What is not written about to quite such an extent is how to develop a disruptive innovation if you are indeed deeply embedded within an existing and well functioning business.

A flourishing industry of independent consultants, authors, coaches and facilitators will train you in the latest techniques required to push disruptive innovation, fresh from the presses of the latest fashionable publication. Many attempt to translate tools and techniques from the entrepreneurial ecosystem straight into a corporate structure.

I’m sure the executive boards of these corporations get a great deal out of these perspectives. However, the trouble starts if you labour to innovate deep within the structures of a corporate culture.

Unless very specific and detailed provision has been made, if you act like a start-up an entrepreneur or a disruptive innovator a great deal of this material that deals with the topic of innovation will get you ignored, side-lined, labelled, and if you are really disruptive, fired.

Innovation may tank your career.

And for good reason. In a well established business that serves a well understood customer with a well understood value proposition, do busy colleagues really want to hear about your disruptive new idea?

Much of the activities to be found within an established business are devoted to the mitigation of risk. This is how the business stays in business. This is what keeps everyone’s mortgages paid and food on the table. Managers are promoted because they offer a safe pair of hands within which to cradle the fortunes of the business.

It is often claimed that in a well established organisation, innovation is everyone’s business. Disruptive innovation therefore often mixes with the gen pop of other technical work required to evolve the incumbent product line. Each compete for funding and resources on a level playing field in that exercise yard.

No-one wants to see your exciting new business model canvas if the organisation is already in possession of a complex and carefully crafted business model.

No-one wants to hear about the new market that you have identified, if the organisation is already flat out serving a well populated and very satisfied existing market.

No-one wants to divert money and resources away from the development of an existing product line that serves an existing and very satisfied customer to a wild idea that may, or may not, work.

No-one wants to risk the reputation of the business, nor the ire of the customer, on a disruptive new idea that may fail horribly.

No-one wants to support your intention to fail fast if your intention is to consume their carefully curated funds while failing 90% of the time.

This is a good thing. Consider the time horizon upon which most individuals are working. This is a business working well to ship a product, keep the customer satisfied and mitigate as much risk as possible. Many will be thinking about their performance and appraisal in the short term. If no-one is listening to your next amazing disruptive innovation, it’s likely because they are doing their jobs well.

Christensen was right.

There is a reason why one of the most successful groups of disruptive aerospace innovators, the Lockheed-Martin Skunkworks, were accommodated away from the main business, on the other side of the runway.

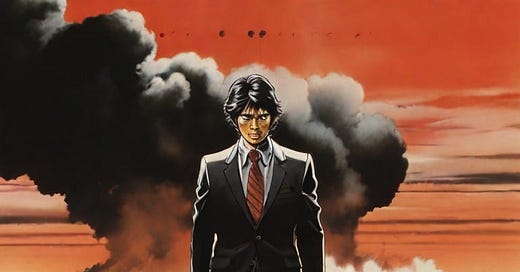

My early attempts to decorate the back of envelopes with designs for the future followed every cliché in the book. After all, the movies that I enjoy often require a technological or scientific creative genius to construct the hero’s Deus ex Machina that will save the day. A naïve approach will simply copy what it sees.

A clever car with an oil slick and smoke screen. A convenient hack into an impregnable computer system. A watch, with a trick. All are fashioned by an eccentric boffin who is ever ready to produce some outlandish innovation at a moment’s notice. If you too can design the future, then with a little more passion and a little more luck the coveted job title of crazy boffin may be all yours.

Unlike the movies, if you play the eccentric boffin in real life it is likely that no one will listen to you. Pulling innovation out of your creative psyche and expecting anyone to value it requires a screenplay that demands that they do.

If you work within a large and well established corporation the reality of innovation is quite different to that of the entrepreneur or chief exec, and quite different to that described in so many start-up or innovation texts. Unless you are the boss, executive board or founder, to pursue innovation under these circumstances requires a more subtle approach to that of explosive disruption.

In The Startup Way Eric Reis observes that entrepreneurs can be found anywhere that people are doing the honourable and often unheralded labour of testing a novel idea, creating a better way to work, or serving new customers by extending a product or service into new markets.

But where did that novel idea come from, and how did it find the support it required to evolve into a real solution to a real problem for a real customer? If the genesis of this idea is to be found in the bowels of a well-established business, how did this disruption gain support? How did this disruption avoid the many antibodies within a corporation devoted to the mitigation of risk?

The works of Reis focus upon the efforts of an innovator to found a new business or recognises that a leader within an established organisation may demand a different approach. At both ends of this spectrum of scale and success, these examples often seem to have already secured the authority to transform the organisation as required.

Injecting more innovative thinking into an established organisation is not automatically associated with the authority to make changes to that organisation. Significant structural changes may only be authorised after you can demonstrate that a new approach will bear fruit. You may not yet possess endorsement from any significant authority within your organisation to make any changes.

You must attempt to adopt new working practices, find new customers and propose radical new product lines between the cracks of the existing structure. You will be judged not on the value of the processes you adopt but on the results of your work. You may in good faith attempt to spot valuable new problems and solutions before your competition. Enthusiasts for this role must recognise that the disruptive voice is not often treated as that safe pair of hands, ripe for promotion.

Reis observes that great ideas sometimes appear in unexpected places. If you labour in one of these unexpected places, then I am writing for you.

If you don’t have support for your ideas from the executive board, if you are not yet authorised nor resourced to engage in a program of innovation, if you only have your own resources to turn to in your effort to conjure up these unexpected ideas, if you work beneath an unremarkable rock at the bottom of a deep corporate ocean and are only as valuable as your last unexpected idea, then I’m writing for you.

If the President of the United States is unlikely to sweep into the room and press his entire executive power behind you and your idea, as is described in one of the anecdotes offered by Reis, then I’m writing for you.

You may be attempting to innovate your way to becoming the next Major Boothroyd or a Lucius Fox with the enthusiasm and creativity that the role demands. If so, I assume that you are a person who needs to solve problems and solve them well. The problems that you wish to solve may have never been encountered before. Alternatively, the problems that you face are long-standing and familiar but now demand a new approach.

Under these meagre circumstances your ideas must be very good if they are to attract any attention at all. I write to help you create those ideas.

A great deal of start up advice doesn't really translate well into the corporate world. There are a great number of traps to stumble into. There are many mines upon which to tread. I have stumbled into many of them, and trodden upon most. If you too are embarking upon such a journey, then perhaps you might appreciate a little warning?

Despite my claims otherwise, I know exactly who my reader is. My reader is me, fifteen years ago.

And perhaps it is also you.

Large becomes small.

Whilst the serpent waited, he would occasionally descend from his tree to search for some variety in his diet. The world was very new, and not everything had yet found its proper place. On one idle departure from his tree the snake encountered a little bird nestling upon the ground.