The engineers shuffled into the conference room, carrying a device between them. They placed this machine gently on the table, and explained how it works.

It was an impressive piece of technology that had required considerable genius to develop. So, he asked his usual question.

What’s it for?

The engineers sighed, and once more explained in even greater detail how the machine worked. He stopped them before they got too deep into their topic. A misunderstanding.

He didn’t want to know how it works. He wants to know why it exists at all. He reframed his question.

What problem do we have that this device solves?

This is usually when the meeting becomes awkward, because once more the engineers have constructed a magnificent solution for which a suitably valuable problem must now be found.

Great.

Here we go again.

You might think that the proper way to devise innovative solutions to difficult new problems is to return to the source. To talk to the customer.

You might be wrong.

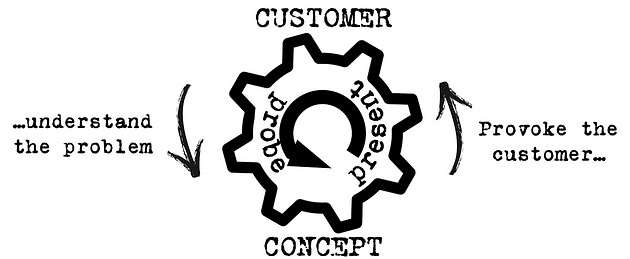

The customer will tell you their woes, and from this you could construct a formal description of their problem.

With this, you could then apply all sorts of interesting techniques to arrive at an elegant solution, about which I discuss often in these articles.

You might brainstorm with raw inspiration. You might define the contradictions and resolve the pair of paradoxes within. You might observe the technical evolutions, and predict the future.

It’s your call, but the source is the customer and their problem. This is where you might start this journey to define an elegant and exciting concept, to feed back to the customer for their approval. This cycle might look like this.

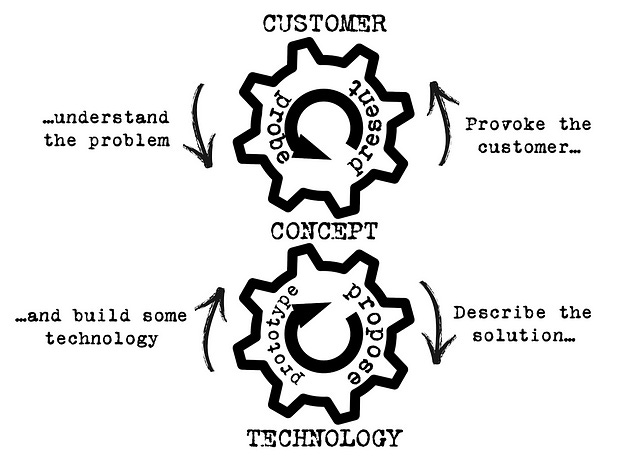

Of course, you can't just keep going round and round this loop. Eventually you have to build something. You package up your concept into a requirement and you present it to those who can transform this into a product.

This might be you. This might be some technical type. Every Jobs has his Wozniak, to whom he proposes an idea and from whom he might hope for a working prototype. This build cycle might try something out, see if it works, feed this back into the concept, and take another try. This cycle might look like this.

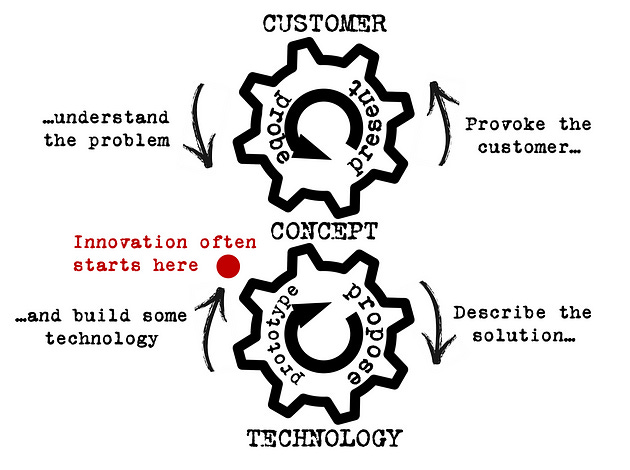

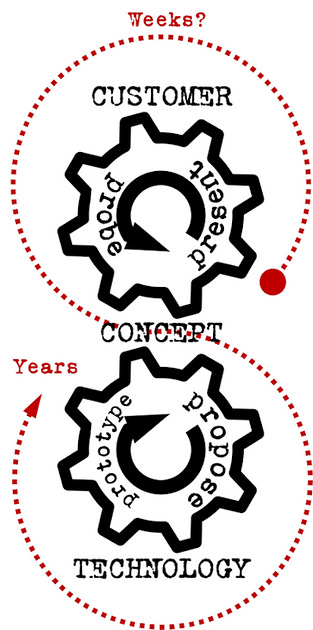

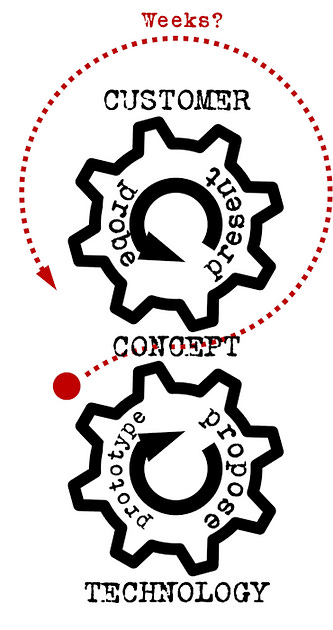

Of course, these two loops intersect at this concept, and are drawn as cogs because each loop can drive the other. This complete system might look like this.

And so we start at the top and we traverse each loop as we must, as if on a journey through the solar system, swinging into the orbit of each loop as the design process demands.

The trouble is, design often does not start like this at all.

If you look out into the world of wild innovation, innovators don’t always start with the customer and their needs. Design often seems to start with a technology. It starts with the solution, and then searches for a problem to solve.

This may be a rough prototype built in a garage. Perhaps it’s the results of research within academia. Perhaps its a complete and functioning product that has caught the attention of a corporate executive board. Either way, there it is, on the desk.

A device, that does a thing.

Who knows why?

Many problem solving exercises start at the exit of the technical build loop. Many innovations are technologies looking for a problem to solve. Many design exercises build the technology, without a complete understanding of the value of this technology. Why?

This seems a ludicrous state of affairs. Why on earth would anyone consider an innovation, the value of which is only vaguely understood? I used to mock those who presented to me solutions for which we now must find a problem to solve.

Then, I realised my error.

Consider how quickly these two processes cycle.

I can interview the customer for a few hours then scuttle back to my office for a few weeks to develop an elegant and devious concept that will fulfil all of their needs. Talk is cheap, as are pencil and paper. This Customer Discovery requires little time and resources.

However, to transform this concept into a requirement and then physically build the solution could take months, or even years. I am a rocket scientist. I work in aerospace design. The development of an innovative new airframe could take decades.

The technology development loop turns orders of magnitude slower than the customer discovery exercise. Therefore, if we start our design process with the customer problem, we may very well be committing ourselves to a decade of research before we eventually arrive at a technology that solves this problem.

Innovation is not about wild imaginative ideas. Innovation is a heavily risk managed activity. Those who hold the purse strings and the authority really don’t like committing to much risk.

The more risk in your proposal, the less likely they are to fund it. The longer the design exercise, the more unknowns and uncertainty over a successful outcome and the greater the risk.

How could we squeeze all of that risk out of our innovation? We could significantly reduce the time required to realise some valuable objective.

We could miss out the Technology Discovery cycle altogether. We could start with technology that already exists, and find a valuable new problem for it to solve.

An innovation programme is likely to present far less risk to the fund holders and those in authority if the programme is much much shorter. If this effort to innovate started with a technology that has already enjoyed years of funding and development, we could be more sure of success.

If we simply selected a solution, and found a problem for it to solve, we are far less likely to fail. Decades become months. Years become weeks. This might not be the most heroic way to innovate, but it may be the most likely to succeed.

This leaves me with a problem.

It is fairly straightforward to brainstorm a new purpose for an old technology using raw creativity and intuition. This is, in fact, often used as an ice breaker in workshops.

Think of ten new uses for a pencil.

However, what is the reliable, repeatable, process for achieving this? What methodology produces hundreds of potential options? How do we connect a technology to an as yet unidentified customer who has an as yet unidentified problem?

I have yet to encounter a reliable, repeatable way to achieve this volume of ideas, detect the most valuable of problems and find the most needy of customers. Feel free to offer suggestions in the comments.

However, what I do know is that if you wish to start innovating at the end of the technology loop, you must start with a technology that already exists.

You could start with a common and very well understood technology from which value and utility have already been much squeezed by many others.

Or you can start with something new.

You could start with the ashes of failure.

You could start with the wrecked dreams of another.

Great Ideas Should Be Disposable

My brother is quite different to me. He is an artist. Always has been. From an early age he had a practised eye and a deft hand. When we were growing up my brother would draw and paint, while I took household objects apart and never reassembled them.