Does technology kill art?

I’m an engineer, and the most valuable tool that I wield is the identification and resolution of contradictions. Paradox can be found everywhere, and the practical mechanisms of civilisation that keep the lights on arise from millions of little compromises to trade between contrary needs.

The world is a mess of paradoxes to be resolved. Contradictions frame the disruptive, difficult questions. To identify a paradox is often the first step to the revelation that we require to realise something entirely new. Once you see the world through this lens, it’s hard to stop. This can lead one to stray from one’s specialisms. To step out of my lane. I have a question. About art.

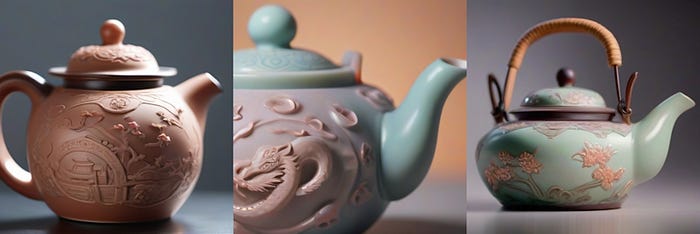

One sight will always provoke me to stop browsing and watch. Handmade Chinese teapots. I’m a rocket scientist, so this field of engineering is quite the departure from my day job. However, to me it is indeed engineering of a sort, and it is fascinating to watch.

Fine clay is pounded and rolled by hand into thin sheets. Metal scribes carve delicate panels from the clay. Intricate stamps gently tap complex characters into the surface. Thin flat sheets are carefully curved with sure hands into cylinders or bowls. Seams are sealed with liquid clays, applied with a pointed wooden stick, to then vanish into the surface. The tiny structure is massaged, tamped, tapped, and smoothed into shape. A lid is constructed, that fits the pot perfectly. Handles and spout come next. No detail is ignored. The tiniest of features enjoy the same attention as the most essential components. Skilled hands transform a lump of clay into a perfect and pristine teapot. It’s an astonishing process, and it’s all achieved without machines.

But what am I actually watching?

I’m not that interested in teapots nor in pottery itself. Am I looking at the moon, or that human finger pointing to the moon? Is the precision with which a human can construct this exquisite pottery by hand the true source of my fascination?

This interest is, of course, not confined to teapots. Handmade automobiles and boats can be beautiful. I’ll happily watch the construction of a log cabin, in the woods. Cookery is a worldwide television phenomenon. Human labour in the pursuit of a perfect performance will always draw an audience, from the finest arts to the muddiest of sports, and everything in between. Would you watch an automated racing car? Would you watch a vending machine cook food?

This is where I find a compelling contradiction.

Consider, for example, that teapot. The artisan is attempting to form the teapot precisely. I assume that each teapot could be formed as precisely as all the others that the artist may craft. A human hand could produce one hundred of these tiny works of art, and if they were all identical we would be astonished. This duplication proves the skill of the artist.

Of course, as I am an engineer, I can think of many ways to make one hundred teapots exactly the same. I could design and construct a mechanism to duplicate millions of them, quickly, and at low cost. If I did this, the value of each teapot would immediately collapse. Who wants a mass-produced teapot for anything other than making a mundane cup of tea?

But even the making of tea is an art.

I assume that the goal of the artist is to build a teapot as precisely as possible. And yet, the value of the teapot is not only in the skilled labour poured into its construction, but in the tiny differences to be found between each attempt. These miniscule variations expose a human presence moulded into the precision of every curve.

A contradiction results. A tension. Whilst the potter attempts to make each teapot precisely, the value we desire is to be found also in the tiny differences between each.

Those differences expose the very edge of human performance. The boundaries of our physical capabilities. The skilled decisions made in the moment. The quirks and personality of the artist, communicated to us through the art.

Find a mechanical means to replicate the teapot exactly, and little value is pressed into that clay.

An intriguing example of this laborious duplication can be found in printmaking. In 1440, Gutenberg created the printing press as an alternative to the exquisite hand scribing of texts by the monasteries. A means to replicate by machine that which, until the 15th century, was made by hands skilled from years of practise. To reproduce the word of God with a mere machine, and not with the hand of a pious man, may have caused some to rankle.

And yet, today the exercise of archaic mechanical methods to reproduce an image thrives as an art form. To operate a manual printing press takes careful judgment, fine skills and chemical alchemy. In printmaking no original work is first independently produced and then presented for reproduction. The artwork is created within the print-making process.

A precursor to a desired image is etched onto a printing plate, typically made from copper or steel, but other materials can be employed. The precise timing of acid corrosion may be used to etch the image onto these metals. Or perhaps the etching is made entirely by hand, with the tip of a sharp tool. Hours can be spent picking the textures from this plate in preparation for the next stage of the process.

The precise quantity of ink applied to this plate is key and demands a practised hand and eye. Ink is carefully but firmly pressed into the plate with the heel of the hand, to laboriously introduce this ink into every hair thin crevice. Once applied, the printmaker cleans the plate of excess, until just enough ink remains to produce a clear impression. If too much ink is removed, the print will be indistinct and insipid. If too much remains, the print will emerge as a dark undifferentiated blot.

The paper onto which the print is to be applied may also be handmade. Each unique sheet the product of another artist. Art works, and artists, combine. This paper must be soaked in water and the moistened surface must be carefully assessed. In this process air humidity plays a part, and the weather itself must be taken into account.

This preparation of plate and paper is then sandwiched between the rollers of a large, iron press. Tons of pressure are wound by hand onto the plate, which leaves an ink impression on the paper. However, the play of pressure upon plate and paper is also a fine judgement that must be arrived at through some initial test pieces. Careful trial corrects tiny error.

Printmaking does not copy a work of art as it does not reproduce an original, existing work. The image is created by the printmaker’s process. The end result that emerges from the printing press is the original work of art. An interesting contradiction, considering Gutenberg’s original objective.

The printing press was conceived to offer many copies of a single image. However, as the printmaker winds the press, these pressures will compress the plate and crush the etching. The printmaker squeezes the life out of the plate that they took such labours to produce. Fine details are progressively lost. The impression they worked so hard to make is destroyed. Only a few prints can be made before the plate is pressed smooth once more.

Ultimately, once expended, the plate is deliberately defaced by the artist so that no more prints can be made. In printmaking, Limited Edition really means something.

As the artist works with this limited resource, they not only attempt to make every copy as similar as their skill permits, but they also work with the little variations in tone that arise from this failing plate. Every print is a clear sibling to the others, but not its twin. In this variation we find the printmaker themselves, and in this we find unique value in each print.

To indefinitely reproduce precise copies of an existing artwork requires quite different technology. The giclée print. This method of producing artworks is a common sight hanging beside those more laborious and necessarily limited editions hand wound from iron presses.

Giclée is described as a fine art technique, but look just a little closer. The French moniker sounds exotic to this English speaker. However, giclée is a French word interpreted into English as ‘to spray’. To spray ink, from a jet.

Inkjet printing.

A giclée printer is a modern, sophisticated form of inkjet printer. It’s a precision piece of digital technology, offering reproductions of extremely high quality and longevity. You can produce thousands of copies of your artwork with this machine without variation at all. With this technology, everyone could own a masterpiece.

Both the enormous reach and competition presented to the artist by the internet offers both opportunity and challenge. You can now connect with more art enthusiasts than ever before, but must make your mark amongst a sea of alternatives. It must be tempting to deliver one’s art to a huge population by digital means to be reproduced on the other side of the world with modern mechanisms.

The next step of this reproductive orgy was to generate and retain the art within a digital format, as employed by the thousands in the craze for non fungible tokens (NFT). Art becomes a financial instrument, and the NFT industry automated the creation of the artwork that was put up for sale which made millions of dollars for some creators. Now that AI can replicate the style of any artist, the artists themselves can now be duplicated with machines.

However, when these digital methods are employed, the human labour that produced the work has long ago left the process. You may indeed now own a digital copy of the artist’s work to hang on your wall, but run your hand across the smooth, sophisticated giclée print and you will not feel the artist’s impression, their unique texture in the moment, those footprints that the artist leaves behind in the work.

The technology is deliberately designed so that every copy will be exactly alike. An ironic testament to the skill of the engineers that created it. And so the tension between the artist’s effort to reproduce a work, whilst we value the very human variations between each, is lost.

Perhaps in half a millennium a master craftsman may be applauded for their attempt to grind a masterpiece from an ancient giclée inkjet printer.

But perhaps not today.

If you would like to learn how to solve difficult problems with clever ideas, this channel or this book could help.